Posted October 04, 2017 in News

Orthognathic surgery , also known as corrective jaw surgery or simply jaw surgery, is surgery designed to correct conditions of the jaw and face related to structure, growth, sleep apnea, TMJ disorders, malocclusion problems owing to skeletal disharmonies, or other orthodontic problems that cannot be easily treated with braces. Originally coined by Harold Hargis, this surgery is also used to treat congenital conditions such as cleft palate. Typically during oral surgery, bone is cut, moved, modified, and realigned to correct a dentofacial deformity. The word “osteotomy” means the division, or excision of bone. The dental osteotomy allows surgeons to visualize the jawbone, and work accordingly.

The operation is used to correct jaw problems in about 5% of general population presenting with dentofacial deformities like maxillary prognathisms, mandibular prognathisms, open bites, difficulty chewing, difficulty swallowing, temporomandibular joint disorder pains, excessive wear of the teeth, and receding chins. Many surgeons prefer this procedure for the correction of a dentofacial deformity due to its effectiveness.

Surgery

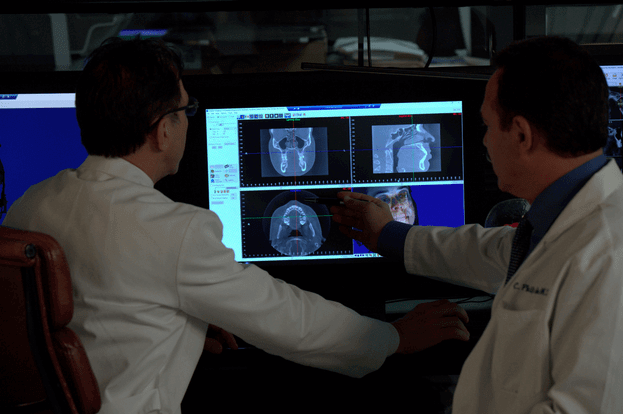

Orthognathic surgery is performed by an oral and maxillofacial surgeon in collaboration with an orthodontist. It often includes braces before and after surgery, and retainers after the final removal of braces. Orthognathic surgery is often needed after reconstruction of cleft palate or other major craniofacial anomalies. Careful coordination between the surgeon and orthodontist is essential to ensure that the teeth will fit correctly after the surgery.

Planning

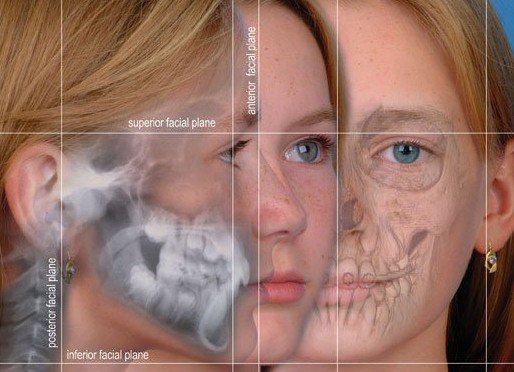

Planning for the surgery usually involves input from a multidisciplinary team, including oral and maxillofacial surgeons, orthodontists, and occasionally a speech and language therapist. Although it depends on the reason for surgery, working with a speech and language therapist in advance can help minimize potential relapse. The surgery usually results in a noticeable change in the patient’s face; a psychological assessment is occasionally required to assess patient’s need for surgery and its predicted effect on the patient. Radiographs and photographs are taken to help in the planning. There is also advanced software that can predict the shape of the patient’s face after surgery, which is useful for the planning and also explaining the surgery to the patient and the patient’s family.

The main goals of orthognathic surgery are to achieve a correct bite, an aesthetic face, and an enlarged airway. While correcting the bite is important, if the face is not considered, the resulting bone changes might lead to an unaesthetic result. Great care needs to be taken during the planning phase to maximize airway patency.

Technique

All dentofacial osteotomies are performed under general anesthesia, causing total unconsciousness. General anesthesia allows surgeons to perform dentofacial osteotomies effectively without involuntary muscle movement or complaints about minor pain. Prior to any Osteotomy, third molars (wisdom teeth) are extracted to reduce the chance of infection. Dentofacial osteotomy is usually performed using oscillating and reciprocating saws, burs, and manual chisels. Reciprocating saws are straight and are used for making straight bone cuts. Oscillating saws are angled, to different degrees, in order to make deep curved cuts for certain osteotomies like mandible angle reduction. The recent advent of piezoelectric saws has simplified bone cutting, but such equipment has not yet become the norm outside of the most developed countries. The surgery might involve one jaw or both jaws cuncurrently. The modification is done by making cuts in the bones of the mandible and/or maxilla, and repositioning the cut pieces in the desired alignment. This surgery is usually performed with the use of general anaesthetic and a nasal tube for intubation. The nasal tube enables the teeth to be wired together during surgery. The surgery usually does not involve cutting the skin. Instead, the surgeon is often able to go through the interior of the mouth. Cutting one bone is known as an osteotomy, while performing the surgery on both jaws simultaneously is known as a bi-maxillary osteotomy (cutting the bone of both jaws) or a maxillomandibular advancement.

Post operation

After orthognathic surgery, patients are often required to adhere to an all-liquid diet. After time, soft food can be introduced, and then hard food. Diet is very important after the surgery; it greatly helps in accelerating the healing process. Weight loss due to lack of appetite and the liquid diet is common, but should be avoided if possible. Normal recovery time can range from a few weeks for minor surgery, to up to a year for more complicated surgery. For some surgeries, pain may be minimal due to minor nerve damage and lack of feeling. Doctors will prescribe pain medication and prophylactic antibiotics to the patient. There is often a large amount of swelling around the jaw area, and in some cases bruising. Most of the swelling will disappear in the first few weeks, but some may remain for a few months. The surgeon will see the patient for check-ups frequently, to check on the healing, check for infection, and to make sure nothing has moved. The frequency of visits will decrease over time. If the surgeon is unsatisfied with the way the bone is mending, they may recommend additional surgery to rectify whatever may have shifted. It is very important to avoid any chewing until the surgeon is satisfied with the healing.

Maxilla Osteotomy (Upper Jaw)

This procedure is intended for patients with an upper jaw deformity, or with an open bite. Operating on the upper jaw requires surgeons to make incisions below both eye sockets, making it a bilateral osteotomy, enabling the whole upper jaw, along with the roof of the mouth and upper teeth, to move as one unit. At this time, the upper jaw can be moved and aligned correctly in order to fit the upper teeth in place with the lower teeth. Then, the jaw is stabilized using titanium screws that will eventually be grown over by bone, permanently staying in the mouth.

This procedure is intended for patients with an upper jaw deformity, or with an open bite. Operating on the upper jaw requires surgeons to make incisions below both eye sockets, making it a bilateral osteotomy, enabling the whole upper jaw, along with the roof of the mouth and upper teeth, to move as one unit. At this time, the upper jaw can be moved and aligned correctly in order to fit the upper teeth in place with the lower teeth. Then, the jaw is stabilized using titanium screws that will eventually be grown over by bone, permanently staying in the mouth.

Mandible Osteotomy (Lower Jaw)

The mandible osteotomy is intended for those with a receded mandible (lower jaw) or an open bite, which may cause difficulty chewing and jaw pain. For this procedure cuts are made behind the molars, in between the first and second molars, and lengthwise, detaching the front of the jaw so the palate (including the teeth and all) can move as one unit. From here, the surgeon can smoothly slide the mandible into its new position. Stabilization screws are used to support the jaw until the healing process is done.

Sagittal Split Osteotomy

This procedure is used to correct mandible retrusion and mandibular prognathism (over and under bite). First, a horizontal cut is made on the inner side of the ramus mandibulae, extending anterally to the anterior portion of the ascending ramus. The cut is then made inferiorly on the ascending ramus to the descending ramus, extending to the lateral border of the mandible in the area between the first and second molar. At this time, a vertical cut is made extending inferior to the body of the mandible, to the inferior border of the mandible. All cuts are made into the middle of the bone, where bone marrow is present. Then, a chisel is inserted into the pre existing cuts and tapped gently in all areas to split the mandible of the left and right side. From here, the mandible can be moved either forwards or backwards. If sliding backwards, the distal segment must be trimmed to provide room in order to slide the mandible backwards. Lastly, the jaw is stabilized using stabilizing screws that are inserted extra-orally. The jaw is then wired shut for approximately 4–5 weeks.

This procedure is used for the advancement (movement forward) or retraction (movement backwards) of the chin. First, incisions are made from the first bicuspid to the first bicuspid, exposing the mandible. Then, soft tissue of the mandible is detached from the bone; done by stripping attaching tissues. A horizontal incision is then made inferior to the first bicuspids, bilaterally, where bone cuts (osteotomies) are made vertically inferior, extending to the inferior border of the mandible, thereby detaching the bony segments of the mandible. The bony segments are stabilized with titanium plates; no fixation (binding of the jaw) necessary. If advancement is indicated for the chin, there are inert products available to implant onto the mandible, utilizing titanium screws, bypassing bone cuts.

When a patient has a constricted (oval shape) maxilla, but normal mandible, many orthodontists request a rapid palatal expansion. This consists of the surgeon making horizontal cuts on the lateral board of the maxilla, extending anterally to the inferior border of the nasal cavity. At this time, a chisel designed for the nasal septum is utilized to detach the maxilla from the cranial base. Then, a pterygoid chisel, which is a curved chisel, is used on the left and right side of the maxilla to detach the pterygoid palates. Care must be taken as to not injure the inferior palatine artery. Prior to the procedure, the orthodontist has an orthopedic appliance attached to the maxilla teeth, bilaterally, extending over the palate with an attachment so the surgeon may use a hex-like screw to place into the device to push from anterior to posterior to start spreading the bony segments. The expansion of the maxilla may take up to 8 weeks with the surgeon advancing the expander hex lock, sideways (← →), once a week.